The first time I heard something along the lines of, “We all need to see ourselves represented,” I scoffed and thought, “No I don’t.” I was a child, and my default was to be contrary. What was the big deal about “seeing ourselves” on screen or in books? Most of the stories I read and movies I watched had nothing whatsoever to do with disabilities, and I still enjoyed them. Related to them, even. While one part of me refused to understand the significance of “representation” and what being represented meant, the other part of me pounced on anything that was remotely disability-related.

As a kid, I found Mine for Keeps, by Jean Little. Published in 1962, it was a bit dated, but it did have a protagonist with cerebral palsy. I think it was the first fictional story I read about a girl with CP.

Then there was Karen: a true story told by her mother, from 1952. I don’t remember much from this one, either, just that Karen chose clear nail polish when she was finally allowed to wear it, so that she didn’t draw more attention to her spastic hands. (Fair warning, if you do pick this one up, apparently it’s quite religious in a 1950s, Catholic sort of way.)

One book I really loved, and still love is How It Feels to Live With a Physical Disability by Jill Krementz, published in 1992, when I was eleven. Krementz interviewed a bunch of kids with a bunch of different disabilities, and in this book they tell us about their lives. Born that way or in an accident, they just tell it like it is, and I loved reading about them, studying the black and white photos over and over again. Because you can stare when it’s a photo. Scrutinize the fingers emerging from shoulders, gaze at those drooping eyes, that residual limb, marvel at the blind girl taking piano and dance lessons. So many ways of being different. A kid with CP is included, and I liked seeing my disability in there, among all the others.

Many people’s first and only cultural reference for cerebral palsy was Geri from The Facts of Life (1979–1988). Geri Jewell appeared in the second season for twelve episodes and was the first disabled actor to have a recurring role in a TV series. (They did not renew her contract.) This was in 1980, before I was born, and I never did see the show. My first memory of someone with a disability on TV was Corky from Life Goes On (1989–1993), who had Down syndrome. At my school, “Cork” was used as an insult. I loved Life Goes On, and I remember how the show stretched my ideas about people with intellectual disabilities when Corky married his girlfriend, Amanda. Oh, how my heart ached for them as they struggled to prove they could live independently and they had a fight about undercooked pasta.

I can vividly remember from my childhood several film experiences that featured a character with a “disability.” Heidi, The Secret Garden, and Pollyanna come to mind. Both Heidi and The Secret Garden star a spunky main character with a friend who is sickly for vague reasons and who uses a wheelchair. With help from their optimistic and determined friends, these poor creatures work hard and learn to walk again. Pollyanna herself is briefly incapacitated before she, too, learns to walk again. Although these “walking again” scenes felt uncomfortable to me, I knew these movies were both historical fiction and outdated at the time that I watched them.

Then came Forrest Gump. It was 1994, and I was in the eighth grade when I went to see this film in the theater. Wow, was I surprised when Forrest screwed his eyes shut and remembered his first pair of shoes. He wore braces! Apparently, he wore them because his spine was “curved like a question mark,” which didn’t make any sense to me, but whatever. When he taught Jenny how to hang from the tree, I thought, “Now, how did he get up there and get himself in that position? And how is he going to get down?” But, whatever. Then, we all know what happened next. Forrest ran. He ran out of his braces, in a slow-motion moment. And I sat there in the dark, feeling frustrated, almost betrayed. “That’s not how wearing braces works,” I thought.

In each of these instances, disability is a plot device, a character development. Something to overcome. Triumph over. Leave behind. That’s what audiences want to see. That’s what we are conditioned to value. Imagine that’s the message you absorb about a big part of your identity, over and over again. A part of your identity that you cannot outrun.

So, what about movies about people with cerebral palsy? At least with CP, we can be sure the character will still have the disability in the end. Off the top of my head, we’ve got My Left Foot: The Story of Christy Brown (1989) and Rory O’Shea Was Here (2004).

My Left Foot is excellent, based on the book by Irish writer and painter, Christy Brown (1932–1981). I was fascinated that his CP left him with one controllable body part, his left foot, which happens to be my least controllable body part. Daniel Day-Lewis famously received an Academy Award for the role. Rory O’Shea is the story of Michael, who has CP, and Rory, who has Duchenne muscular dystrophy. They are both power chair users and live in a home for the disabled. If you know anything about Duchenne, you know this movie ends up being really sad, but before it’s sad, it’s funny. Michael succeeds at getting independent housing and a live-in (?) carer, and Rory accompanies him as his interpreter because Rory is the only one who can understand Michael’s speech. (Don’t ask me why Michael doesn’t have better assistive technology). Neither of these actors has a disability, and there was actually noise made over why actors with disabilities weren’t cast in the roles. (I wonder if anyone posed that question about Daniel Day-Lewis in 1989?)

Then there’s The Usual Suspects (1995). If you haven’t seen this movie and don’t want to be spoiled, skip this paragraph. I watched this movie as part of an American Studies class as an undergrad. I don’t know why it was in the running; I voted for an episode of The West Wing. I remember nothing about this movie except that Kevin Spacey’s character has mild CP and I was surprised and intrigued. And then in the final scene as he walks away, his arm and hand straighten and his limp disappears and he is the villain. They use my disability as a disguise. As a way for someone to commit crimes and get away with it. To make everyone think he is weak and meek and incapable because he is disabled. And he is smug and chilling and I hate this movie. This movie makes me angry. Remember how I thought that at least if there’s someone with CP in a movie, it won’t be just a plot device? At least they’ll still have CP in the end? Angry. Disgusted. Frustrated. Spacey won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

The message that movies send us over and over is that life is better if you’re not different from the norm. But difference isn’t bad. Difference is part of existence. Disabilities are part of being alive. Disabilities are normal. Let me say that again: having a disability IS NORMAL. It’s part of who we are as a species on this planet. We are born with disabilities and we can acquire disabilities at any time in our lives.

According to the CDC, the country’s largest minority group is people with disabilities, with 26% of adults having some type of disability, both visible and not. So where are we? Where are we in the stories we create and release to audiences around the world?

People who’ve always seen themselves reflected on screen have probably never thought about representation, because they’ve never had to wonder where the people like them are. (Looking at you, straight, white, able-bodied men.) If we are in any way an Other–and chances are, many of us are Othered in more than one way because most of the people on this planet are not straight, white, able-bodied men–then people will have formed ideas about our Othernesses based on representation in the media. We all form ideas, judgments, opinions based on what we consume and what we are exposed to. Books, TV, movies, music, magazines, advertisements–if you’re not represented there, how does the world know you? If you are not visible, how can you be seen?

In her 2009 talk on the danger of a single story, author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie states, “The single story creates stereotypes. And the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete.” If people with disabilities are only portrayed as the inspiring sidekick who will overcome, that leads to able-bodied people feeling surprised that people with lifelong disabilities have jobs and spouses. That limited story is why the world has people who ask utterly ridiculous questions like, “Do you sleep in your wheelchair/with your leg on?” Clearly, the general public needs to see more–more authentic and more positive–depictions of people with disabilities in all media, if only to normalize our existence.

Recently, I learned about identity-conscious casting. I watched a video essay by Khadija Mbowe who explored colorblind versus identity-conscious casting. (It is excellent and Khadija is awesome, and I really like their videos.) Much of the next several paragraphs I have borrowed from their essay.

The idea of colorblind casting, or nontraditional casting, has been around since the 1980s. Actors Equity defines nontraditional casting as “the casting of ethnic, minority and female artists in roles in which race, ethnicity or sex is not germane to character or play development.” So, if the role doesn’t require a specific race or sex, it’s open to anybody.

In 1986 (after discovering that 90% of stage productions from a four-year stretch had all-white casts) Actors Equity sponsored the first National Symposium on Non-Traditional Casting, where they focused on ethnicity (LA Times article). Nontraditional casting has been a goal since then.

In recent years, we’ve evolved to be more color-conscious rather than colorblind: “Color-blind casting (or non-traditional casting) is the practice of casting without considering the actor’s ethnicity, skin color, body shape, sex, and/or gender. Color-conscious casting, then, is the opposite of color-blind casting: taking into consideration the actor’s skin color, body shape, and other characteristics.” We as humans do see race, and “we should always acknowledge it, on or off the stage” (delshakes.org).

The second Actors Equity symposium, held in 1990, dedicated its second day to disability inclusion, as issues around casting actors with disabilities had been absent from the first symposium. While nontraditional casting had at first focused on race and gender, it began to expand, and our language has continued to evolve as well.

Now we have identity-conscious casting, which recognizes intersectionality. Not only should we always acknowledge race, but also gender identity and disability, and everything an actor brings to a role.

Victor Vazquez, founder and casting director of X Casting NYC, says, “The power of imagination is exactly what casting is. I think the American theatre struggles to understand this work: casting as imagination, casting as a culture-making machine” (howlround.com). Or as Khadija Mbowe so succinctly summarizes: “Casting is culture-making.” We create our culture through what we make, and who makes it. By the stories we tell.

When we see intersectional diversity on screen, it helps us understand what is possible, or what exists that we’ve never thought about. We don’t always know what we haven’t been seeing until we do finally see it. (For example, I had never seen a doctor wearing a hijab until Grey’s Anatomy, and it had never crossed my mind that I hadn’t.)

Let’s return to disability representation on television since the second Actors Equity Symposium in 1990. Now, I did not have cable growing up, nor was I allowed to watch much TV. Just in case I need to make a disclaimer that this is not a comprehensive discussion on disability in television, consider it made.

I remember Dr. Kerry Weaver in ER (1994–2009) and Dr. Gregory House in House (2004–2012). A forearm crutch and a cane. Just a limp they both had, just enough to make their characters more nuanced. Of course, both roles were portrayed by able-bodied actors.

Two other medical shows, one a daytime soap and one a night time soap, did hire actors who used wheelchairs in real life. Port Charles had Dr. Matt Harmon from 1997 to 2000, played by Mitch Longley. Longley became a paraplegic as a teen. I think this was the first time I’d seen a doctor in a wheelchair. He also had a romantic relationship with another doctor, a black woman. I was keenly aware that theirs was an interracial, interabled love affair, and so were the characters. (Though I’m not sure the term “interabled” existed in 1997.) Yes, they had the “Yes, I can have sex” conversation that every wheelchair user seems to be confronted with, that people seem to feel it’s okay to ask outright. Private Practice (2007–2013) included Michael Patrick Thornton as Dr. Gabriel Fife for fourteen episodes between 2009 and 2011. Thornton uses a power chair and has partial use of his hands. His character was rather arrogant and meant to be controversial. Good for them for showing that people with disabilities can be assholes, too, I guess? Interestingly, his love interest was also a black woman doctor, and they also had the “Yes, I can have sex” conversation, if I remember correctly.

Why all the medical shows with disability rep? And where are the women? And nonwhite people? That said, I was always happy to see any kind of disability representation, and watched those scenes extra closely. Grateful for every crumb. Disability representation should be so much wider than a crutch or one full-time wheelchair user as a small part of a large cast. It has always felt like tokenism.

Five years after Dr. Fife exited Private Practice, ABC brought us Speechless (2016–2019). This one is a family comedy starring Micah Fowler as JJ DiMeo. This was a big, groundbreaking deal. JJ (and Micah) has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair, and the premise is that JJ will have an aide, Kenneth, at school who will help him communicate. If you catch yourself thinking that someone with cerebral palsy playing someone with cerebral palsy doesn’t sound much like acting, stop and ask yourself if you’ve ever had that thought about a straight, able-bodied guy playing a straight, able-bodied guy. I was curious about the show, of course, so I gave it a try. I think I only made it through the first or second episode. I like shows that have at least a little believability at least some of the time. After Kenneth helped JJ try on clothes from the lost and found to get a new look, and they montaged through a head-to-toe cowboy outfit and several others, I just couldn’t take it. Let’s set aside that none of those brand new clothes would ever be in a lost and found. Think about helping someone with a moderate-to-profound physical disability fully undress and dress over and over again. At school. You’d both be exhausted, sweaty messes. That’s a nope for me. Even though there might have been good CP-related content in the series, the overall tone and humor were also definitely not for me.

Netflix then came out with Special (2019–2021), a show for adults written by Ryan O’Connell, who has CP, too. I heard this show was about a guy who gets hit by a car and pretends that’s why he moves differently. I really don’t like the word “special” to refer to someone with a disability, and I really don’t like the idea of lying about your disability, so I gave it a pass. Until now, for this post. I watched the pilot last night, and it was a rather awesome fourteen minutes. The show opens with Ryan face-planting on some uneven sidewalk, answering a child’s inquiries by rote (great way to get the exposition in there!), going to physical therapy, musing about his place in the disability world as an ambulatory CPer, and struggling to extricate himself from a table-and-bench situation. It was flippin’ fantastic! I have never seen those experiences (my experiences) on screen before. Wow. It turns out that seeing yourself reflected on screen is rather powerful. I hadn’t understood that as a child because I had never experienced it.

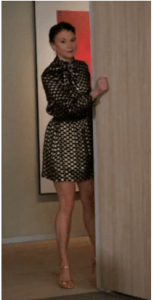

Over the last year or two, I rewatched the series Younger (2015–2021). I will not talk about the disappointing final season, but I will talk about Sutton Foster. As I watched one twenty-four-minute episode flow into another for hours, I studied Sutton Foster.

Sutton Foster is 5’9”. She is very obviously dressed to accentuate her long, slender limbs. Given that her character, Liza, is forty, trying to pass as a millennial at a publishing house in New York, her costume designer must have had lots of fun. Over Younger’s seven seasons, Liza does indeed wear some bizarre outfits. And lots and lots of short skirts and tall heels.

I often find myself watching actors do their walk-and-talks. I notice the way they enter and exit rooms, especially if they’re on their way out, and then turn and pause in the doorway. Or if they’re on their way in and they turn and close the door behind them. Then they have to turn back around and keep going. I watched Sutton Foster do all these things many times.

She is graceful, a talented singer and dancer with great comedic timing. I tried to imagine her character wearing ExoSyms or AFOs or using forearm crutches or a walker. How those elements would change her wardrobe or alter a scene. How she would look. The way she would move. A physical disability on this character would change everything, you see. The timing for everything would be different, slower. A witty line tossed over the shoulder as she leaves the room wouldn’t land the same way. Never mind sex scenes, or fancy-dress events with dancing or drink-carrying, scenes outside on grass or sand. Scenes with stairs.

Watch a show. Imagine the lead wearing braces and using crutches or a walker, so that their hands were occupied with helping them walk. How would the show be different?

In 2020, Lifetime released Christmas Ever After, starring Ali Stroker as Izzi Simmons. Ali Stroker won the 2019 Tony Award for her role as Ado Annie in Oklahoma!, becoming the first wheelchair user to win a Tony. I was excited to see her new movie because I remember Ali from her time on The Glee Project (2011), and it’s so awesome to see her in bigger roles. Is this a great movie? No, it’s a Lifetime Christmas movie, and it’s just what you’d think it is. The spectacular thing about this movie, though, is that Izzi Simmons’s disability isn’t the story. I don’t think they even mention it. There’s no tragic past accident that made her afraid to love again, blah, blah, blah. No, she is a novelist with a deadline, and that’s the story. Even though it’s probable that her wheelchair use would come up when meeting new people, I like the choice not to make it part of the story. An able-bodied actor could have been cast in the role, but wasn’t.

So how is this movie different because Ali plays the lead? There are simple, obvious adjustments, like those acting opposite her pulling up a chair or sitting on the stairs. When Izzi goes to bed, she falls asleep on top of the covers rather than taking the screen time to maneuver her legs beneath the blankets.

And yeah, just as I suspected, Izzi’s entrances and exits are a little different, a little awkward, even. But she’s startled, astonished, and acting a little odd because the man she meets looks just like the protagonist in the romance series she’s writing, so it works. She runs away unexpectedly, still talking as she goes, arms moving quickly to make a hasty exit.

This Lifetime movie got so much (positive, of course!) press for starring a disabled actor. In 2020. Thirty years after that Actors Equity Symposium focused on disability inclusion.

In September 2020, Disability Scoop summarized the findings from a report by the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism: “Across five years of data on disability representation, the researchers said that ‘no meaningful change was observed in the percentage of speaking characters with disabilities.’ Moreover, not a single film in the 500 studied since the researchers began tracking disability inclusion featured speaking characters with disabilities in numbers comparable to their prevalence in real life.”

In episode two of ABLE, actor-comedian Maysoon Zayid is interviewed about her experiences as someone with cerebral palsy in the entertainment industry. When asked, “How do you feel about disability representation in the media? And what needs to change?” she gives a great response: “I think it’s extremely, extremely offensive when actors who are nondisabled play visibly disabled on screen. I think it’s cartoonish. I think it’s inauthentic, and I think that much like race, disability that is visible cannot be played. And the reason I use the word ‘visible,’ is that we actually have no idea how many people with invisible disabilities grace our screens. Because the stigma against stuff like, you know, mental health issues, chronic pain–it’s so strong that even stars don’t want to reveal their diagnoses. People with disabilities–we’re the largest minority in the world–we’re only two percent of the speaking images you see on TV. Of those two percent, ninety-five percent are played by nondisabled actors. That fact that. . . we are part of every single group is often ignored.” Yes, Maysoon! Nothing about us without us! Actor, advocate, and disability inclusion consultant Christine Bruno takes it one step further: “It shouldn’t be ‘nothing about us without us.’ It should be ‘nothing without us!’”

Twenty-six percent of adults live with a disability. A quarter of all characters on screen and in print should live with a disability as well. It doesn’t have to be all that they are, just as real people are complex and intersectional. It is powerful to see your own experience on screen. Especially if you don’t know anyone living with the same conditions that you do. To see a character on screen like you, showing you that you are not alone, showing all viewers that people like you exist, it normalizes our vast and varied lives.

If we saw people with congenital limb differences, for example, in our favorite TV show, we would know that limb differences aren’t so different. Perhaps then we would not have the maddeningly recent, horribly offensive utilization of the real-life condition ectrodactyly in the newest adaptation of The Witches, as an attribute to make the witches more wicked and scary. We need to normalize disabilities, not use them to promote harmful stereotypes! How did this unnecessary change to the original story go forward with no objections? Perhaps if 26% of the people involved in making this movie had had disabilities, it would not have happened.

Here’s another, very different example, just to make you think about something you may never have before. To remind us all that there are people out there, living with conditions that we may never have heard of, who deserve to have their experiences reflected back at them as valid and valuable. Approximately 1 in 500 Americans live with an ostomy, a surgically created opening in the body for the discharge of body waste. That waste is then most often collected using a pouch system. What if a character had an ostomy and a pouch that they had to monitor and change, and it occasionally came up as part of their everyday life? What if that person had a healthy sex life and participated in sports? If you or someone you love developed Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis and were facing an ostomy, perhaps it wouldn’t seem so foreign or scary because you had a cultural reference.

We have so far to go to achieve true inclusion in arts and entertainment. Creators of film and television have such an incredible opportunity to reach people, open minds, expand views, and increase understanding and acceptance of our amazing array of differences. It shouldn’t be revolutionary or newsworthy to hire people with disabilities and to tell our stories. We’re here. We matter. Representation matters.

Notes and References:

I know of two other movies, starring women with cerebral palsy, that I did not discuss: Margarita with a Straw (2014, India) and 37 Seconds (2019, Japan).

ABLE: the series Watch this series about disability inclusion in the entertainment industry for free on YT! I really enjoyed it.

Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts

Cinemability: The Art of Inclusion

Shondaland.com:

“The 1in4 Coalition is Cracking Open Doors for Disabled People in Hollywood”

Deadline: SAG-AFTRA Panelists Say “Disability Consistently Overlooked In Conversation About Diversity & Inclusion”:

https://deadline.com/2021/04/sag-aftra-panel-disability-hollywood-actors-gains-1234735412/ This article from April, 2021, summarizes the current state of inclusion nicely.

Respectability.org:

https://www.respectability.org/hollywood-inclusion/

Disability Scoop:

The Iris Center:

https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/resources/films/

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The Danger of a Single Story

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg

Khadija Mbowe: Color-blind vs. Identity-Conscious Casting

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYTN6BnK_KI

The Limb Difference Community Reacts to The Witches Movie