Training Day Four: Thursday, 18 June. 9:30–12:30, 2:15–4:00.

I wake up on this morning, having had enough upper-back-tension pain yesterday, in the night, and this morning–and knowing that I won’t have the knee sections–that I just want to get today over with. With these two significant bumps in the road, I’m feeling done. Ready to rest. But I have to do it.

What a doozy.

Ryan texted last night and this morning to check on my back. At the clinic, he asks how I’m doing. I tell him I’m doing better than yesterday. Pain is about a four. He does not like that at all and talks to Jared about having more of a recovery day. I am a little surprised. A four is pretty good. I thought we’d do the regular stuff, with fewer reps. But they seem intent on trying to help the pain go away. This belief that we can successfully improve the pain is a little bewildering to me. Especially here, with all the military connections, I figured it would be a “Work through the pain!” kind of environment.

Jared and I stay in a side room with parallel bars. He asks if I’ve ever had an adjustment. “Like at a chiropractor? No.” I’ve thought about it, but I’ve never been comfortable with that whole relax-on-command-even-though-you-know-I’m-about-to-do-something-sudden-to-your-body idea. He describes what he’s proposing, assures me no one has ever had a bad experience with it, and asks if I’d like to try it. Sure, might as well. I stand between the bars and put my hands behind my head (that is a challenge). Then he stands behind me and somehow reaches around me and up behind my head too. I then lean back into him, give him all my weight, and crack, crack, crack, he lifts me off my feet for a second. And one more time, crack crack. Do I feel much different? No. But it is satisfying to hear all those cracks.

We stand against a wall with the parallel bars in front of us. He wants me to flatten the small of my back against the wall (knees bent), and then push against the bar to flatten my back all the way up, doing a kind of chin tuck at the end to stretch out my neck. It’s really hard to maintain the pelvic tilt and do all the rest. The bar is a little too far away for me to use it effectively. Jared tries attaching big foam bolsters around the bar to make the distance smaller. When that doesn’t work, we spend a lot of time taking this huge long bar out of its three legs, flipping it over so it extends toward me more, and trying to get it back into its three legs at the same height again. All so I could push off of it to do a stretch that I can’t really feel stretching anything. This chin-tuck neck stretch is something I was given years ago. Why am I not just lying down to do this?

He asks about the (semi) daily stretches I already do, several for the upper back and shoulders, and quads, calves, hamstrings, and hips. “Well, those all sound good.” Yes, and even though I’ve improved at them, my body doesn’t feel noticeably better.

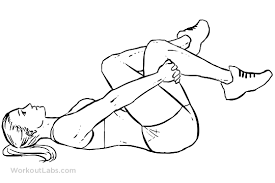

We go out into the gym to work on the exercise my physical therapist calls, “T-bar with bobble head.” At home, I lie on a yoga mat, knees bent, arms straight up, Theraband in my hands. I then take my arms out into a T until my hands reach the floor. Shoulder blades are back and down “in my back pocket.” Once I’m in the T, I shake my head. This is to get the neck to relax while still engaging the traps. My shoulders blades are squeezed together, chest out. Does my neck relax? No.

Jared has me try variations of this. I lie down under a parallel bar. He drapes a giant, thick, stretchy band over the bar. It has so much resistance, I can barely move it. He has to add an extra loop so it’s longer.

I try lying on a foam roller. It supports my spine while my feet stay on the floor. But it rolls too much for me to balance well. (Or, I am unable to balance well, so it rolls too much.) Jared tells me to carefully lower myself to the floor. I scoot/roll/slide gracefully off the roller. “Or that,” Jared says. Hey, that is “carefully lower” in CP Land.

They don’t have a half roller anymore because it got destroyed as an element in obstacle courses. So Jared improvises with a line of spiky half ball things up my spine. I like these. They feel pretty good.

“I’m realizing that’s about as high praise as you give,” Jared says.

Well, I mean, ExoSym training week is not a place for tons of great fun. Maybe for other, once-able-bodied people. Not for CPers with spastic diplegia. I do ten reps with the band on the spiky balls.

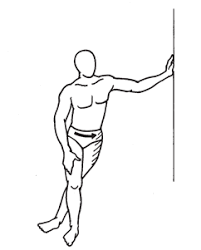

Jared also shows me a standing piriformis stretch that I really like. See? Really like. You stand on the side you want to stretch and cross the other leg over (or the picture shows behind) the standing leg. Then you just stick your hip out and twist your upper body until you feel a good stretch. I twist and bend over the parallel bar, holding on with both hands.

So much easier than getting down onto the floor and somehow achieving the right amount of stretch by pulling on my own leg. “It’s a good stretch, and I don’t have to get on the floor,” I say, wondering why no one had shown me this before.

“I’m sensing that’s a big thing with you,” Jared remarks.

At first I’m surprised that it’s not immediately clear that getting down onto and up from the floor is indeed a big thing with me, but then I remind myself that although Jared can see the way I move–and understands the mechanics very well–that doesn’t mean he knows what it feels like to operate this body. I wonder if he’s familiar with Spoon Theory?

It’s time to get to walking again. Jared talks about putting all my weight on the stepping leg and swinging the other one forward–letting the device swing it forward if I’m doing it right. We talk about my poles. Apparently, I haven’t been moving opposite arm and leg together consistently. I’ve been doing Pole. Foot. Pole. Foot. Four separate movements. I know I’ve had the poles pretty far out in front of me to create a wide base for stability, like the four legs of a chair. But this instinct has me leaning forward, straining my arms, and not keeping my weight into the devices. I understand that I need to be standing straighter, with the poles closer to me. It makes sense. That doesn’t mean I can actually do it yet.

Jared shows me options for pole technique. Poles in unison, like a skier. (Nope.) Or alternating hand and foot, like I thought I was doing. He wants me to keep my elbows by my sides and angle the poles back, which puts my wrists in a much better position. “Use them to propel you forward!” I’m not ready to be propelled forward. I completely understand the why behind this method. But I cannot do it. When I angle my poles back, I cannot move. I cannot step forward with the support behind me instead of in front of me.

Jared continues to explain and encourage, and I keep trying, taking deep breaths, emotions running high. I do not have the balance or strength yet to move this way. I put my poles back again. “There! That’s good!” he says, even though my lower body has not moved. I feel one hundred percent truly and actually stuck with the poles in the “correct” position.

Have you ever had the experience of helping a child with math, or something else they struggle with? You’re explaining with enthusiasm, thinking it’s rightfully complex but things are going well, and then the child is crying. Frustrated? Overwhelmed?

I keep trying to breathe through my feeling of “I literally cannot do this.” I try to simply let him know my present reality of “I don’t have the stability to do this right now.” The tears come anyway. I am grateful that my mask and glasses cover my weepy face and my snot.

Jared politely ignores the tears and acknowledges my struggle. He wonders if it’s a mental block/fear.

I say, “Maybe partly, but it also feels legitimately physical.”

He asks if I’d be willing to try it in between the parallel pars, lowered to hip height and positioned closer together. Yes, of course, I’ll try again. Jared leaves me in the safety of the bars and goes to meet another patient. I am able to use the bars to steady myself without letting go of the poles, so I’m more comfortable trying the new technique. But I still really struggle with the mechanics of it all with my muscles so weak.

I’ve only been at it a few minutes when Ryan stops by to check in and release me from this PT session. He asks how I’m doing.

“Physically, better. Emotionally, it’s been a tough day.”

“What about it has been tough?”

“Trying to do stuff I just can’t do yet,” I answer, getting a bit teary again. I always say “yet” or “right now.” I understand I am at the beginning.

Ryan acknowledges that I have emotions to process. “And I’m all for that.” He reminds me again that it’s a process. That I’ll be sending videos to him every week, that he’ll still be there. He wants me to know that I’m doing well, that I’m actually doing better than other CP cases he’s had. He assures me of this. Asks how I feel about it.

When it’s clear that he’s waiting for an answer, I say, “Um. Well, it’s kind of irrelevant because we’re not supposed to compare ourselves to people.” I would have liked it to come out more eloquently than that, but it didn’t.

I wasn’t upset that I was doing badly or that other people had done better. I wasn’t upset that I couldn’t do this thing. I’ve lived my whole life with limitations. I have no problem recognizing my limits, and I had no delusions that they would disappear. It wasn’t that I couldn’t do it–I’ve got that down. I was overwhelmed because all of Jared’s effort, expertise, enthusiasm, and good intentions were focused on me alone, and I was being asked/urged to do these things right now. I needed more practice, more time, to process and to try, without pressure.

Ryan tells me to go eat and rest and that I’m welcome to come back after lunch. “How do you feel?”

“Right now I don’t want to,” I acknowledge. “But I know I need to use this time.”

“You don’t have to.” He really means it. “I’ll leave it up to you.”

Of course I have to come back. We didn’t come all the way here for me to decide to not keep working.

I switch to my regular shoes and Dad and I walk back to the hotel. I am able to use my poles slanted back and alternating on this walk. After lunch I go straight to sleep, still feeling emotional. I wake up with drool on my pillow. Good nap.

In the afternoon, Dad walks me back to the clinic, and I go in alone. I change into my ExoSyms in the lobby and manage to put my backpack away in the room with the cubbies (first door on the right) by myself and make my way across the gym. I have the room with the really short parallel bars, a chair at one end. I practice with the poles between the bars. I’m able to do the slanted thing somewhat, sometimes.

I realize that what I need is to fall. I need to experience a fall. I need to know what it sounds like–carbon fiber clattering together–and what it feels like. It needs to be somewhere I know I can get back up. Not here, on linoleum. In the ExoSyms, even with poles, several times a day, I have the full-body clench, loss-of-balance moment, but so far I’ve caught myself. A fall will happen. The certainty of it looms, couched in suspense and the unknown.

Ryan checks in and advises me to step and squeeze my glute, really focusing on a good heel-toe on the left. I set aside my poles, and I am left alone to practice between the parallel bars. Six steps. Turn. Posture. Relax toes. Again. Trying to do hips forward like Jared said and glutes like Ryan said. Calm and careful. Feeling better.

I just needed time and a safe space to make friends with my devices. Slow, curious. No hurry. No audience or analysis. I stand between the bars, spend time learning how far forward or backward I can shift my weight before my balance goes. Yes, I can let go of the bars and raise my arms when I’m alone.

I practice getting my weight over my hips and keeping it there with each step instead of hinging forward. Squeeze each glute. Put all the weight into one foot, and let the other swing through, heel-toe. Forge new neural pathways. Walking feels different when I successfully use these techniques. Not so much like cement ski boots. Good different. Better.

I walk up and back for about an hour and a half, taking pauses in the chair. I feel like I can start experimenting with taking one hand off the bar. My left side locks up and I can’t swing my right leg through. But a few times I get it. Two steps with just one hand hovering over the bar before I lose it.

If I move my arms like a power walker, it helps me keep my forward momentum, even though my left leg wants to tense up and halt everything. I have a tiny taste of achieving an actual walking stride. I try again and again. I’m just finishing a full length of the bars with no hands when Ryan checks in.

He is properly excited for me and praises my accomplishment with feedback: “What you did with your arms looked better than with your sticks!”

I do a few more laps with poles to continue to try to coordinate those, already stiffening up and losing my rhythm. Ryan, like Jared, suggests putting my hands through the straps and twisting the straps to give my wrists support. I mention my concerns about falling with my wrists through the straps. “Don’t fall,” he says. If that isn’t perfect able-bodied advice.

I get the right ExoSym adjusted again because the heel still burns. Fortunately, it doesn’t take an hour this time, and then we walk back to the hotel.

Food, ibuprofen, journal, meditation, sleep. Day four complete.